The Worldwide Destruction of Our Cultural Patrimony

by Gerry Schaus

After Alistair Edgar’s excellent presentation on March 25 about the political aspects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it seemed appropriate, if not so immediately concerning, to consider a lesser aspect of this conflict, but one that’s part of a global phenomenon, the destruction of our—meaning all humanity’s—cultural patrimony, through war, religious and political zealotry, treasure hunting, environmental damage, and other causes. Here, we’re talking about the significant remains from past human activity preserved to humans now, and for the future, if only we care to protect these remains.

This is a topic of far-too-great a scope for a 45-minute presentation, so the focus of my presentation on April 22 was to convey the massive size of the problem through just a few examples, some current and well-known to most people, others less-well known from the past, and ones that I have experienced in the course of my field work.

Fig. 1: Marble statues from Persian destruction 480 BCE, Acropolis museum

With the attack by Russia in late February this year, Ukrainians immediately sought to protect their cultural treasures, especially in Lviv, their cultural capital, by moving them to safer quarters, for example, in the Sheptytsky National Art Museum, or just by wrapping statues protectively where they stood in city squares. Some 2,500 years ago, the Athenians failed to do this when the Persians, under King Xerxes, invaded Greece. The result was horrendous vandalism of statues and buildings all over the Acropolis. Now, of course, we can tell ourselves how lucky we are to be able to enjoy these great treasures preserved surprisingly well from the past because Athenians buried the ruined monuments as garbage when the Persians left. But it took 2,350 years for us to find these discarded treasures, clean and conserve them, and put them back up on display in the Acropolis museum (see Fig. 1).

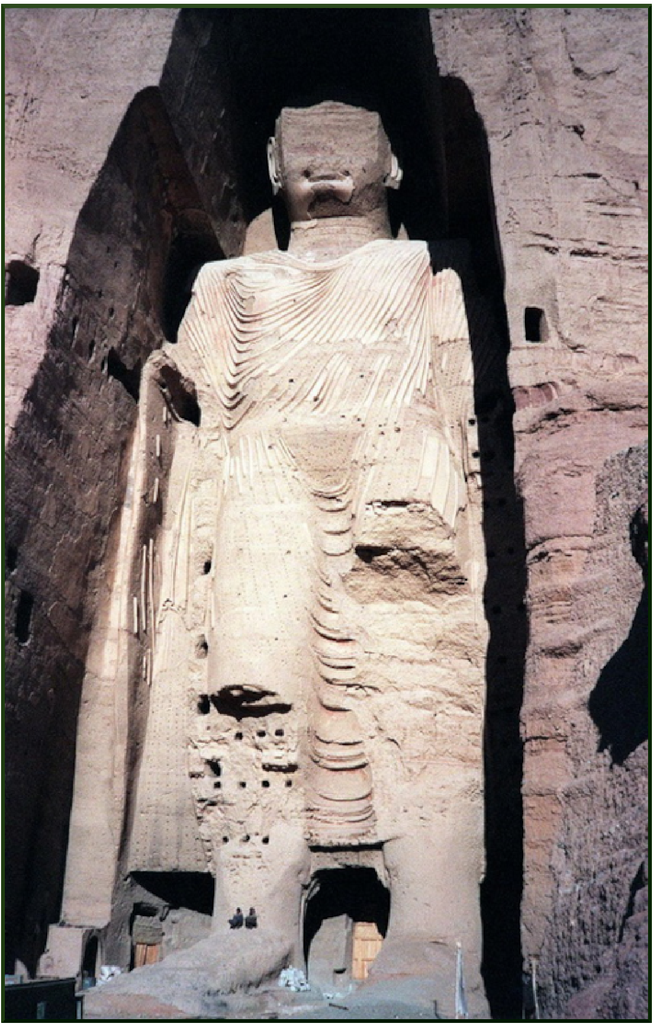

Fig. 2: Giant statue of Buddha, Bamiyan, before destruction

Twenty years ago, two magnificent giant statues of Buddha dating back to about 600 C.E., located in Bamiyan, an isolated district of Afghanistan, were totally destroyed by Islamic fundamentalists, since the Taliban regarded them as examples of idolatry. The fate of these world-heritage figures saddened the hearts of many around the world. Now the Afghanis, deeply regretting what they did, are allowing UNESCO and other organizations to rebuild the Buddha statues from the small fragments that remain. You just shake your head (Fig. 2).

Ten years ago, while with a group of Laurier archaeology students on the Black Sea coast of Romania on a training dig, I was scheduled to give a lecture on a Sunday afternoon. The talk was delayed for two hours for reasons unknown to us waiting at the hotel. It was because Romanian archaeologists coming for the talk discovered a professional couple, one a surgeon and the other a lawyer, using a metal detector on the site we were digging. They were using the detector to find antiquities for their own personal collection at home in Vienna! The two of them could have been sentenced to ten years in prison for this theft and destruction, but instead, they were fined and required by police to sit in the front row of my lecture to hear what I had to say about the important results of proper archaeological field work at ancient Stymphalos. It’s the only time that criminals have been punished by having to attend one of my lectures. I hope they learned their lesson (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Amateur metal-detector looters at ancient Argamum, Romania

It’s at Stymphalos where I’ve come across four more types of cultural destruction in recent years. One was deliberate vandalism of sturdy information signs describing the results of our excavations in the residential part of the ancient city for any visitors who came by. A second instance was a local farmer ploughing up an area near the famous lake, home to the mythical Stymphalian birds, clearly in an archaeologically-protected zone. This was done as much out of spite against archaeologists as for any productive agricultural purpose. A third was wide-spread digging in several parts of Stymphalos where the operators of a metal-detector had illegally found metal objects close below the surface and decided to dig them up. Ancient coins were likely their primary goal, but any metal objects, including jewelry, would be welcome, no doubt. In any case, the illegal intrusions ruined the top strata in various swaths for any future archaeological work.

Fig 4: Looters’ tools left behind at the cave sanctuary, Stymphalia

The worst example of cultural destruction in that region has taken place over the past thirty years at a rich cave-sanctuary site, isolated near the top of Mt. Oligyrtos, overlooking the valleys of ancient Stymphalos, Orchomenos, and Pheneos. Here, looters of the sanctuary site have systematically excavated deep and wide trenches, moving hundreds of cubic meters of soil, in search for buried treasures, most likely so they could sell them on the black market (Fig. 4). Greek authorities have known about this illegal work since 1994, but haven’t been able to protect the site because it’s so inaccessible. My fourth visit to the site this past October revealed just how bad the on-going destruction has been. A Greek friend who runs the small village ethnographic museum in nearby Lafka, has tried for years to salvage some of the thousands of fragments of figurines, jewelry, cult bric-a-brac and pottery left behind by the looters in their spoil heaps, just so we would have some knowledge of the votive gifts left at the site in antiquity and what the looters may have taken home as a reward for their despicable destruction (Fig. 5).

Fig 5: Salvaged terracotta figurines from the cave

These are all sad examples of the permanent loss of our cultural heritage, but they are just minor examples of what’s going on all around the world, every day, year after year. Most of this destruction goes on undetected and unpunished, certainly without there being sufficient deterrents to stop it. The Greek archaeological service visited the cave sanctuary again in 2020 after a new report of recent looting reached their ears. They painted a red circle with an X within it on the cave wall to show that it’s a protected site! Austrian friends climbed up to see the site later in 2020 after we told them what was going on, and they left behind a goat’s skull mounted on a stick right beside the red circle. Pardon my lack of faith in voodoo as a means to discourage looting, but the options are limited, and in desperation, we’re sometimes willing to try anything.